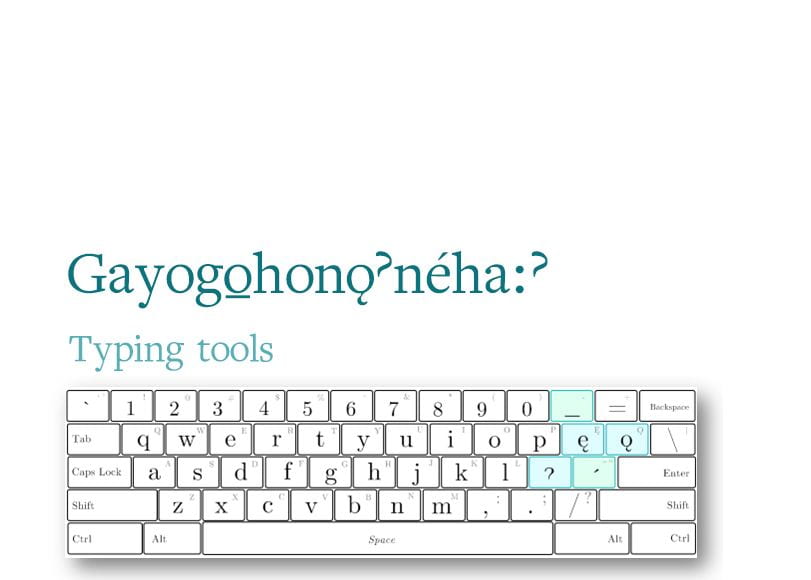

The Gayogohó:nǫˀ Indigenous people (named -mispronounced- Cayuga by the English and American settlers) have a longstanding relationship of more than 13.000 years with the Cayuga Lake region, where the main campus of Cornell University is situated (Cornell University, 2021). This history includes a critical and painful event in 1779 when soldiers from the American armed forces carried out the Sullivan-Clinton expedition (Figure 1). This military attack had the purpose of destroying the Onǫdowáˀga:ˀ (Seneca) and Gayogohó:nǫˀ (Cayuga) settlements and crops from peoples who were supposed to be allies of the British during the American Revolution (Jordan, 2022). American history celebrates this expedition as a victory “against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians”. For the Gayogohó:nǫˀ, on the other hand, it was a genocide against their people and their culture, and one of the leading causes of their diaspora. However, it did not mean, and neither did the continuous and systematic colonial attacks, their disappearance. The Gayogohó:nǫˀ have a contemporary presence, and their struggles to preserve their culture and reconnect with their territories continue.

Figure 1. Map of Sullivan’s expedition showing the settlements and crops destroyed, with a Zoom in the Tompkins County region. Source: modified from (Map of Gen. Sullivan’s march from Easton to the Senaca & Cayuga countries., 1779)

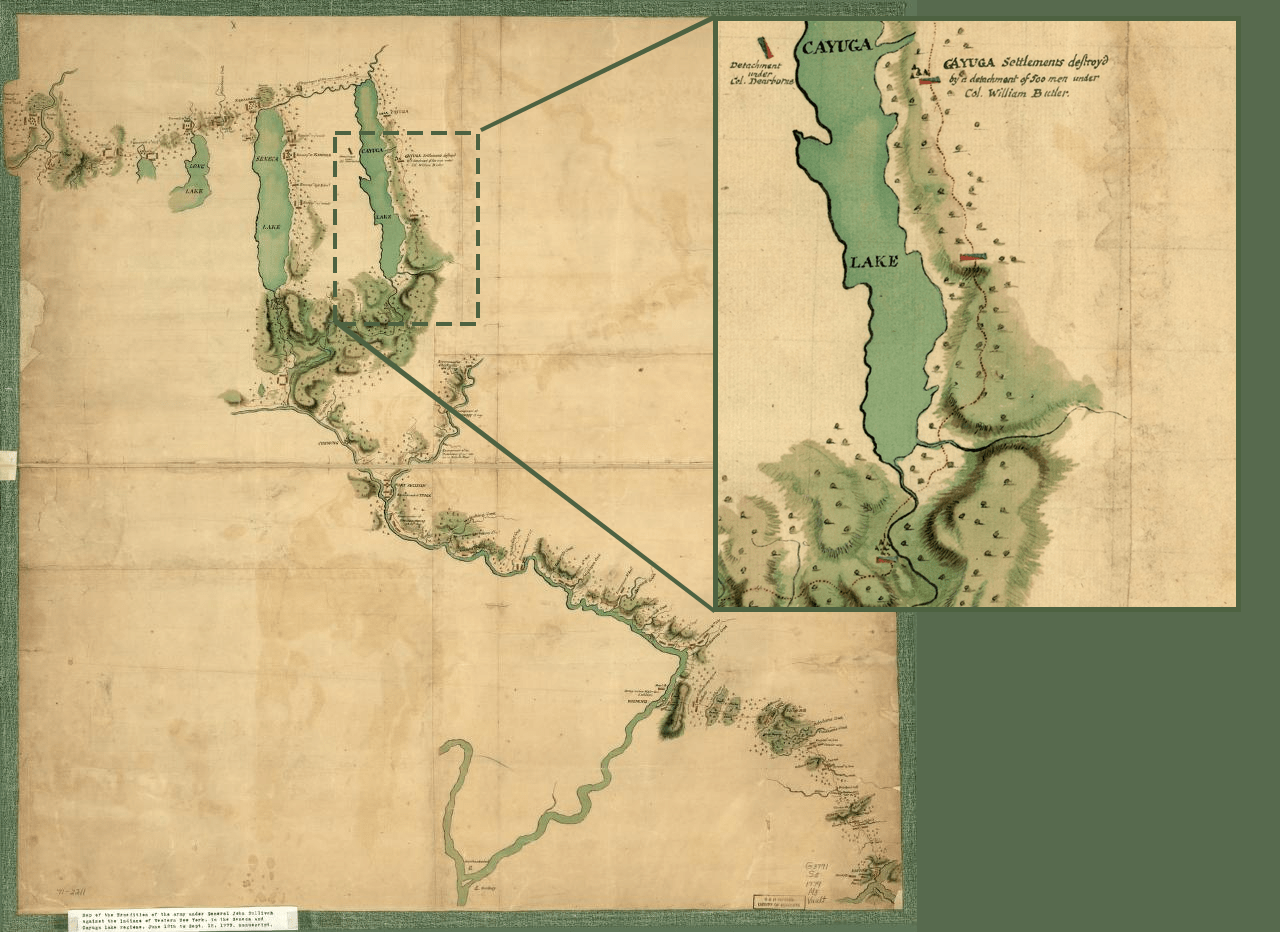

Stephen Henhawk is a dedicated member of the Gayogohó:nǫˀ community, who is actively involved in their struggles. He considers that preserving Gayogohó:nǫˀ language is crucial to protecting their culture, unraveling their history (Figure 2), and safeguarding their ways of living and co-existing with nature. Worryingly, the number of people who speak Gayogohó:nǫˀ as a first language is less than ten, Stephen being one of the youngest (Sanders, 2024). This short number is the reason why the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization declared Gayogohó:nǫˀ language as critically endangered (but not extinct).

Figure 2. Map of the Cayuga Lake region where Stephen Henhawk matched their oral traditions, thanks to the descriptive quality of Gayogohó:nǫˀ language, with the landscapes he saw when he came back to their homeland. Source: Stephen Henhawk.

According to Jordan, “(t)he Gayogohó:nǫˀ community asserts that wider use of Gayogohó:nǫˀ by outsiders will help their own efforts to revitalize their language.” (2022, p. 5). Following this statement and concerned about the difficulties in digitally writing and reading Gayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ, this work presents a set of tools that aim to support Gayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ and English typing, especially for second-language learners. Currently, typing Gayogohó:nǫˀ requires copying and pasting from a well-spelt source and makes the writer lose the writing flow. Also, many readings of Gayogohó:nǫˀ on the web present misspelled words or use different typography that disturbs the aesthetics of the text and provokes the sensation of Gayogohó:nǫˀ words “not belonging” to the entire writing (e.g.: https://lrc.cornell.edu/news/coming-home-gayogohono-language-programs-expand-reach-0).

Gayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ, the Gayogohó:nǫˀ language

Gayogohó:nǫˀnéha:ˀ is a very descriptive language ( Gayogohó:nǫˀ Learning Project, 2022) that reveals straight relationships with nature and with their homeland (Fiorello, 2021). For example, Gayogohó:nǫˀ (Cayuga) means “from the swampy land” (Jordan, 2022), and Hyáikneh (June) literally translates to “fruit ripen” (Dyck et al., 2024). Regarding its structure, Gayogohó:nǫˀnéha:ˀ has three kinds of words: nouns, verbs, and particles (that have diverse uses like adverbs, pronouns, conjunctions, among others), and uses seven vowels (a, e, i, o, u, ę – nasal e -, and ǫ – nasal o -) and thirteen consonants (d, g, h, j, k, n, r, s, t, ts, w, y, and ˀ-glottal stop-). Vowels may include an accent mark (á, é, í, ó, ú, ę´, and ǫ´) that indicates more emphatic pronunciation of the marked syllable. Vowels also could be underlined (a, e, i, o, u, ę, and ǫ) meaning that they are whispered, almost inaudible. Additionally : is used as a slow marker (Dyck et al., 2024; Gayogohó:nǫˀ Learning Project, 2022).

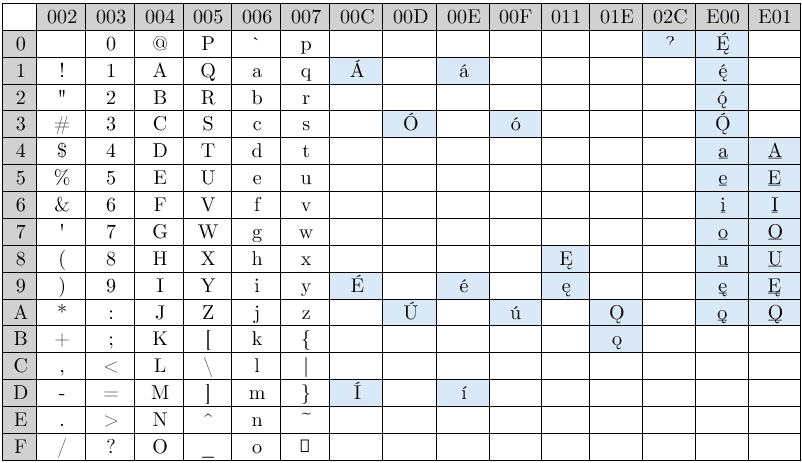

Tool 1: Unicode list

Unicode is the most used standard for encoding text. Table 1 presents the set of Unicode main characters used to type English and Gayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ. The code for a character results from concatenating “U+”+ <column title>+<row title>. For example, A is U+0041, and ˀ is U+02C0. Characters in the last two columns are in the group of private use and encode custom Gayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ characters without replacing existent standard symbols.

Table 1. Unicode list that includes characters to type in Gayogohó:nǫˀ (especial characters highlighted in blue) and English.

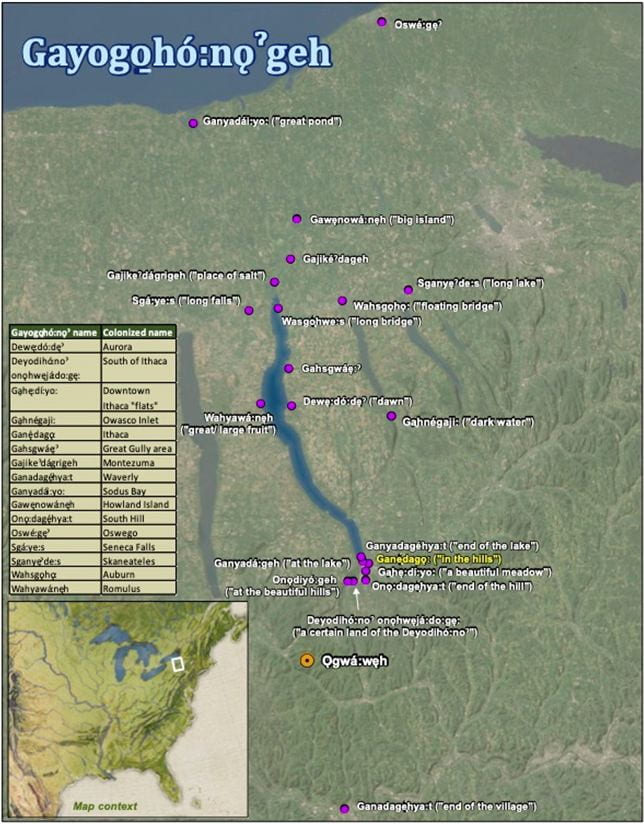

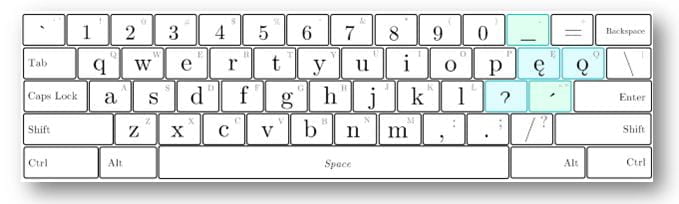

Tool 2: Keyboard layout

Recent projects like First Voices aim to support and promote Indigenous languages. They provide diverse resources, including keyboards, and within these, there is one for Gayogohó:nǫˀ (Cayuga). This keyboard layout, however, overwrites characters used in English, like the c (replaced with ǫ) and the v (replaced with ę). This tool proposes a keyboard layout (Figure 3) that responds to the Unicode set in Table 1. It’s important to clarify the design audience of this particular keyboard. This design centers those who do not speak Gayogoho:nǫˀnéha:ˀ as a first language but rather second language speakers or simply those who incorporate Gayogoho:nǫˀnéha:ˀ into their writing alongside English. If we were to center a different user, such as Gayogoho:nǫˀnéha:ˀ first language speakers, the design outcome and structure would most definitely alter.

Keyboard for Windows:

https://github.com/ljcortesr/Gayogoh-n-/blob/main/Keyboard%20layout%20gayoengl.zip

Figure 3. Keyboard layout. In blue, special characters for Gayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ typing. In green, modifiers for vowels; to use them in composed characters, modifiers should be typed first, and then the vowel.

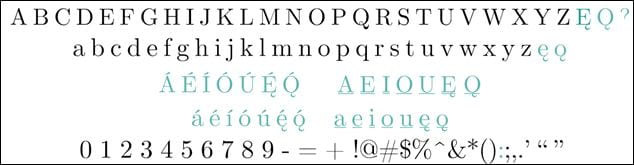

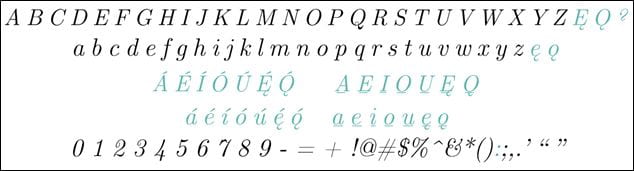

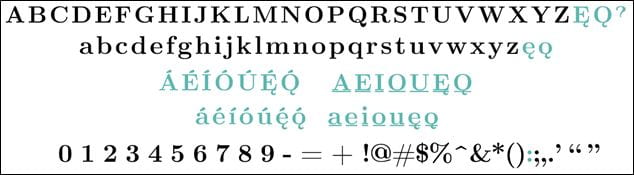

Tool 3: Font family

The proposed font is called Węna Gayogohó:nǫ. Węna means ‘word, voice, speech’. It is a Modified Version of Computer Modern (original family of the TeX typesetting program), including the special characters ofGayogohonǫˀnéha:ˀ, licensed under the SIL Open Font License.

Węna Gayogohó:nǫ Font:

Gayogoh-n-/Wena Gayogohono Font.zip at main · ljcortesr/Gayogoh-n- · GitHub

Węna Gayogohó:nǫ Regular

Modified from Computer Modern Serif Roman (CMU Serif)

Węna Gayogohó:nǫ Italic

Modified from Computer Modern Serif Italic (CMU Serif Italic)

Węna Gayogohó:nǫ Bold

Modified from Computer Modern Serif Bold (CMU Serif Bold)

Imagining possibilities

TCAT (Tompkins Consolidated Area Transit) provides public transportation throughout Tompkins County, the homeland of Gayogohó:nǫˀ people. TCAT routes cover the territory using the names given by the settlers. Using a 5×7 dot matrix font that includes Gayogohó:nǫˀ special characters and matching Stephen Henhawk’s map (Figure 2) with TCAT routes, the next set of images proposes also displaying Gayogohó:nǫˀ names over existing infrastructure in the buses as a recognition of Gayogohó:nǫˀ historical and contemporary presence in the territory.

Acknowledgments

SHUM 6683 Class -Spring 2024-: Disturbing Settlement -Engaged-. Professor Amiel Bize.

Stephen Henhawk talks: Naming places and Gayogohó:nǫ Learning Project.

Carlos Aranzazu: Fonts’ design.

References

Cornell University. (2021). Land Acknowledgment. American Indian and Indigenous Studies. https://cals.cornell.edu/american-indian-indigenous-studies/about/land-acknowledgment

Dyck, C., Froman, F., Keye, A., & Keye, L. (2024). A grammar and dictionary of Gayogo̱hó:nǫʔ (Cayuga). Language Science Press.

Fiorello, S. (2021). Collaboration plants seeds for cultural, biological conservation | Cornell Chronicle. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2021/09/collaboration-plants-seeds-cultural-biological-conservation

Gayogohó:nǫˀ Learning Project. (2022). Gayogohó:nǫˀ Language. Gayogohó:nǫˀ Learning Project. https://gayogohono-learning-project.org/language

Jordan, K. (2022). The Gayogohó꞉nǫˀ People in the Cayuga Lake Region: A Brief History. Tompkins County Historical Commission.

Map of Gen. Sullivan’s march from Easton to the Senaca & Cayuga countries. (1779). [Map]. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3791s.ar106400/?r=0.083,0.928,0.288,0.149,0

Sanders, K. (2024). Gayogohó꞉noˀ Speakers Work to Restore Language Among Cornell, Nation Communities—The Cornell Daily Sun. https://cornellsun.com/2024/03/06/gayogo%cc%b1ho%ea%9e%89n%c7%ab%cb%80-speakers-work-to-restore-language-among-cornell-nation-communities/, https://cornellsun.com/2024/03/06/gayogo%cc%b1ho%ea%9e%89n%c7%ab%cb%80-speakers-work-to-restore-language-among-cornell-nation-communities/