The Foul Play of Political Geometry in Texas

Over the past year, I have been working alongside Texans Against Gerrymandering to understand how data science tools could help streamline their efforts in generating public awareness for fair redistricting and political mapping practices in the state of Texas. This blog is essentially a contextual dump of material to reflect on Texas’s districting process as a case study in transparency and algorithmic governance.

Background

Tis the season! State legislative map drawers gather in Austin, Texas to play their deciannual numbers game, a meta-chess match with election and census data as their cheat codes. The district mapping process happens every 10 years in the US when the census data is collected and released; legislative members will put forth proposed maps for both the congressional and state levels.

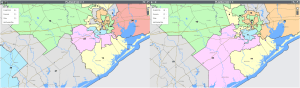

Each redistricting process varies by state. Some states have independent map drawers that are disassociated from the current state legislature. However, within Texas everything is contained in house, even using an exclusive mapping tool called Redistricting Application (commonly known as RedAppl- very ominous), which is not a tool open for public use. Nor are the modeling practices, training sessions or mapping protocols open to the public. If there is a proposed map released to the public, they will do so through the Texas District Viewer tool, but that’s more a visualization portal (see the colorful maps below). There is no state wide tool that allows for the public to submit their preferred community or district maps.

To continue, there are general national rules that the maps must comply with. One being, the population of different districts must all be close to the same, which is why rural districts occupy a much larger land area. In addition the voting rights act Section 2, is a prohibition of voting practices and procedures, including redistricting plans that discriminate on the basis of race. Within the fair maps community there is debate on how effective that prohibition is (Courts rely on “direct intent” to claim there was racist foul play). Some states have state level district mapping requirements and procedures, Texas does not (surprise).

So the complications between transparency issues, state and federal requirements (or lack thereof) is what allows for gerrymandering to occur, which is the manipulation of district voter maps to benefit certain political outcomes. The product of gerrymandering is often these goofy looking shapes that are clearly not reflective of how people define their communities. However, this is not always the case, the output of gerrymandering comes in many geometries, and can be done in various ways such as cracking, packing and hijacking just to name a few.

Below is my hometown of Fort Bend County, which was seen to be one of the most rapidly growing counties in Texas. On the left is the current senate district map, and on the right is one of the newly proposed maps that was released just this past November. You see how District 22 went through a growth spurt, consuming District 27’s area? That is because District 22 is at threat of becoming a democratic district due to population shifts. In order to maintain republican strongholds, District 22 adopted some of District 27’s rural (predominantly white) counties. You can truly witness cracking at play here. Rural counties are not split apart; their boundaries line up with the boundaries of the district maps. However, Fort Bend County is split between three different districts, failing to geometrically adhere to public representation and community ties.

Transparency in District Mapping

Dr. Micah Altman & Dr. Michael McDonald founded the Public Mapping Project in 2001, and helped establish the district builder tool which is an open source software that helps public novice district map makers draw maps that comply with federal regulations. And they state, “The drawing of electoral districts is among the least transparent processes in democratic governance. All too often, redistricting authorities maintain their power by obstructing public participation.” I will be using some of this terminology to now define transparency in a clearer context to what it has been defined as typically when discussing notions of “transparency” specifically in context to algorithmic governance.

What exactly does transparency exactly refer to? If we look at past Texas gerrymandering court cases, usually something complies with traditional notions of transparency when an “entity” is disclosed or semi disclosed. This does not necessarily mean disclosed to the public, but rather disclosed to anyone outside of the entity’s creation or upholding.

There are then several cases in which a transparent process is not necessarily a fair process. Just because the mapping process itself is disclosed, does not ensure that gerrymandering will cease to exist and districts will be drawn fairly. Though it does promote accountability, it unfortunately demonstrates that legislatures will adopt practices that obscure what has been disclosed.

This is something we are actively witnessing at the Texas capitol. In 2020, the Brennan Center for Justice released in 2020 the Redistricting And Transparency: Recommendations. Some of its key recommendations are for authorities to 1) Publish preliminary maps, 2) Accept public comments. Both of which Texas has actually done this drawing cycle. But as we saw earlier with congressional District 22, there are still cases of gerrymandered maps. Why haven’t these acts of disclosure caused uproars in public attention?

Transparency is only as useful as bureaucracy allows it to be. Who is this act of disclosure for? In most of these present and historical cases the answer is not the Texas public, but rather the courts, who have the authority of either rejecting or accepting contested, gerrymandered maps. And who also have the capacity to sift through obscured maps and materials of gerrymandering cases. Lip service transparency.

One method of obscuring is making the materials that are disclosed difficult to obtain or incredibly jargon dense, discouraging the public from participating due to time or a lack of expertise. Another method is by bombarding the legislative agenda with hot topic bills and debates in order to deter public attention from gerrymandering and unfair mapping disclosures and hearings.

You might have heard of some of these hot topics bills because of their controversy, list includes: Senate Bill 8 (Texas Abortion ban at 6 weeks), Senate Bill 3 (abolishing critical race theory in public schools), Senate Bill 1 (which has been called the poll watcher protection bill). And this is just to name a few, all have done an effective job at deterring public attention and participation from gerrymandering and fair mapping topics to highly controversial senate bill subjects. And that is not to criticise Texas constituents and voters, but rather highlight how disclosed material can easily be obscured.

Machine Learning to the Rescue?

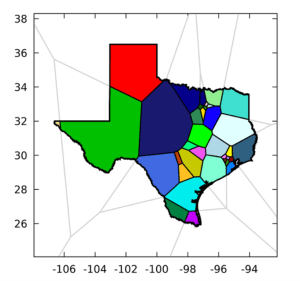

Well, if we cannot implement transparency successfully in currently redistricting structures, can algorithms act as an independent entity that reduces bias in district mapping? Efficient too! I will have to say as a very avid, recently graduated data scientist I thought this could be THE solution, originally approaching this work under the notion that machine learning tactics are the foundation to future fair mapping practices. I began to look at work that involved census data clustering and intensive PDE solution approximation work, all which were great conducive algorithms as you can see from the figure below (Cohen-Addad et al, 2018).

However, I began to question whether or not these algorithmic methods were transparent, aside from being open source. And for the same reason I think highly jargoned legislative reports and bombarded agendas are not transparent, I do not view these algorithms as transparent either. They require high level expertise to be understood and interacted with. They do not combat the obstruction of public participation, nor do they assist public participation. Additionally, to have map generation algorithms that rely solely on census data (which is flawed, both historically and presently- more on that in another post), is to take away the public’s governing agency. It does not allow for constituents and the public at large to input their boundaries and definitions of community.

However, I began to question whether or not these algorithmic methods were transparent, aside from being open source. And for the same reason I think highly jargoned legislative reports and bombarded agendas are not transparent, I do not view these algorithms as transparent either. They require high level expertise to be understood and interacted with. They do not combat the obstruction of public participation, nor do they assist public participation. Additionally, to have map generation algorithms that rely solely on census data (which is flawed, both historically and presently- more on that in another post), is to take away the public’s governing agency. It does not allow for constituents and the public at large to input their boundaries and definitions of community.

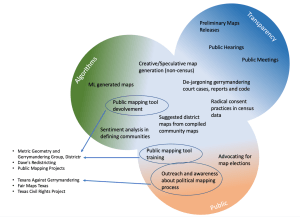

However, I of course do believe there is an important role purely census and machine learning work could play a productive as an element in the fight for fair maps, as does transparency as disclosure. I believe there is space in which the public, algorithmic tools, and transparency efforts and discourse can exist as a set of incomplete infrastructures and temporary solutions that can push, generate and stimulate further work in fair district maps. And in an effort to consolidate all those words I believe it’s essentially… public governance with algorithms.

Community Defined District Maps

There are a number of grassroot groups in Texas working on a variety of subjects that fall in the public and transparency space, Texans Against Gerrymandering, Fair Maps Texas, Texas Civil Rights Project just to name a few. Simultaneously, there are incredible public access geospatial tools that allow for the public to make their own maps and draw out their communities. The Metric Geometry and Gerrymandering Group created Districtr, Dave’s Redistricting, Public Mapping Projects, and there are ongoing collaborations between these grassroots organizations to train residents on how to use these tools.

And that inspires an expansion of these tools, some of the work we are currently conducting includes sentiment analysis of Districtr’s map text boxes. These text boxes allow constituents to briefly elaborate and describe why they included a certain geographic feature to their community. How can we understand how people are linguistically defining community? And because Texas is not a monolith, how are different groups of people wanting their community to be geometrically defined? How do we move from community to political district?

Additionally, we are exploring political geometry (a term coined by Moon Duchin and Olivia Walch from the MGG group) clustering methods to conglomerate and puzzle piecing together individual constituent’s community and potential district maps made in these drawing tools, creating potential district maps that rely on direct public input.

The majority of the existing constituent mapping tools exclusively use census data, which is understandable because that’s what the legislature utilizes to draw maps. However, how can we get creative with this process and create speculative maps that use– restaurant information or peoples commuting patterns (things that are highly integrated in our lives but not contained within demographics), seeking new ways to quantify and geometrically define community, without relying primarily on the census.

There are several shifts occurring due to ongoing lawsuits such as those in Senate District 10 Fort Worth area, so our work is always in flux but we are hoping it will be something useful. And that is to say not a single one of these can act as the Answer to upholding fair district mapping, but a collection of these dynamic, temporary solutions that can keep up to the rapidly changing Texas state could be our greatest form of resilience in advocating for transparency in public governance.. with algorithms.

References

Dryer, Presentation to the Texas Senate Select Committee on Redistricting, 2010 https://redistricting.capitol.texas.gov/pdf/Mapping%20and%20Redistricting_Senate_090110.pdf

Brennan Center for Justice, 50 State Redistricting Informational, 2019 https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/2019_06_50States_FINAL_1.pdf

Kinder Institute, 2020 Census State Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) for Texas , 2021 https://kinder.rice.edu/urbanedge/2021/09/10/2020-census-texas-cities-counties?utm_source=Monthly+Newsletter&utm_campaign=196944b0ab-Urban-Edge-Newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_0d1f6bbea4-196944b0ab-712445836&mc_cid=196944b0ab&mc_eid=e9f0fc8bb7Sourc

Aratani, Secret use of census info helped send Japanese Americans to internment camps in WWII, 2018 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/04/03/secret-use-of-census-info-helped-send-japanese-americans-to-internment-camps-in-wwii/

Seif, DOWN FOR THE COUNT: The profitable game of including immigrants in the census, then deporting them (Texas Observer), 2010 https://www.texasobserver.org/down-for-the-count/

Brennan Center for Justice, 2011, Redistricting And Transparency: Recommendations For Redistricting Authorities And Community Organizations https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/analysis/redistricting%20and%20transparency.pdf

Gonzales et al. , Prison Gerrymandering Report, Texas Civil Rights Project, 2021 https://txcivilrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Prison_Gerrymandering_Report.pdf

Cohen-Addad et al. , Balanced power diagrams for redistricting, 2018 https://arxiv.org/pdf/1710.03358.pdf

Jacobs et. al, PDE approach to defeating partisan gerrymandering, 2018 https://arxiv.org/pdf/1806.07725.pdfv