An Audience With The Box

Nearly two years after I contacted the Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, my schedule finally allowed me to visit the box. The staff invited me to visit while the center was closed to the public, and had a full day of measuring cut out for me, but from what I saw the Cummings Center looks like a phenomenal resource for scholars. The staff were tremendously generous.

Background

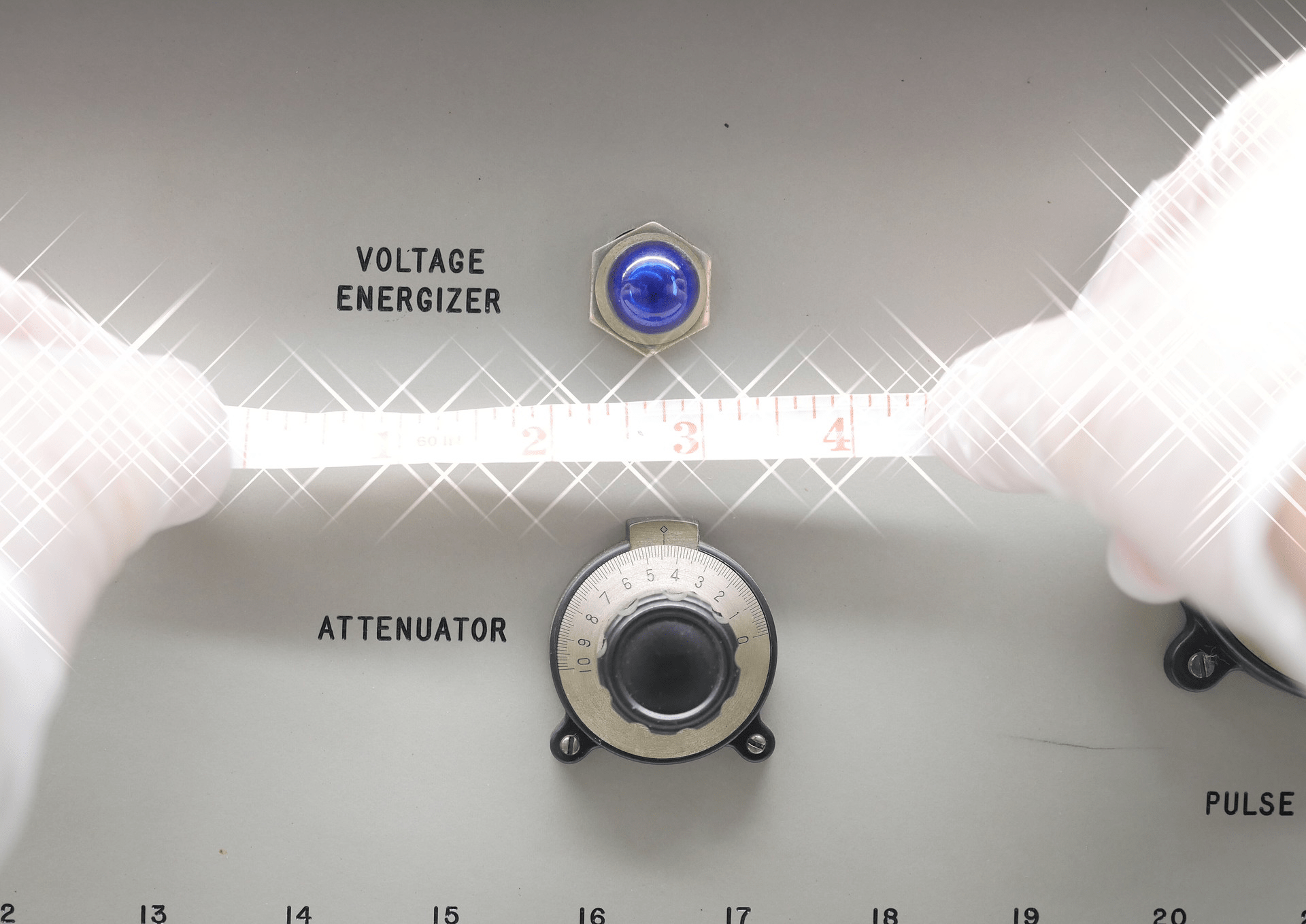

As described in the first post on this project, I’m rebuilding the Milgram box to recreate a contemporary version of the experience of the Obedience to Authority studies, using remote gig labor rather than an actor, and gallery visitors, rather than human subjects. I do want the device to be as accurate as possible. Many of the electrical components used in the box are no longer available, so I couldn’t recreate it exactly. Indeed, the box was apparently rebuilt and changed over time, so I’d also have to choose an arbitrary version of it. Nonetheless, while I can’t achieve complete accuracy, I do want to get as close as possible. Equipped with calipers, rulers, lasers, and camera, I spent the day measuring. But more importantly, I was able to see the materials used, and find evidence of how it had been fabricated, from old tape residue to sloppy welds.

First Impressions

Slogging my kit through the museum entrance, it was a short walk to the elevator, from which my generous host let me 10 feet across the hall to a cold storage room with THE BOX sitting unceremoniously on a small table.

Speaking of pyschology, I have to say that the object affected me quite differently than I’d expected. I tend to not think too much about trips ahead of time; early in my life I learned that things are never what you expect, so while I know people that research and make lists before trips, I tend to prepare the absolute minimum, and try to keep the experience open. Nonetheless, I have read a lot about the experiments and the box itself, and clearly I did expect to measure an old piece of scientific equipment which I’d seen in hundreds of photos and films, and read about extensively. What then was different from my expectations?

Unexpected Measurements

First – and this shouldn’t have come as a surprise – the urge to precision can be thwarted. The box was custom built, by reasonably talented folks, but not engineered so much as hacked. This meant that my efforts to measure ran into a kind of sloppiness of fabrication that I hadn’t expected. The box has a metal top and sides – made from bent steel much like HVAC ductwork, and a faceplate. The metal of the top and sides is drilled to attach the faceplate, but the faceplate is not actually attached the way it was aparrently supposed to be. Unused holes are evenly spaced around, and the faceplate is really just floating behind where it was supposed to be mounted. In other places, holes are misaligned and ended up unused. The jankiness makes it difficult to measure, but also: should I recreate unused holes? Should I attach the plate the way it was originally meant to be attached? I think yes, but it’s not completely clear.

Second, I don’t think I was prepared for how fake the box would be. It’s large, imposing, and scientistic. But as I looked, I realized that the steel construction was exactly the same technique that I’d used in projects I’d done before, when trying to simulate scientific equipment on the cheap. It’s not built like actual lab equipment of the time would have been built. Honestly, an art school student might have built it. The way the sheet metal was constructed is almost exactly the way I made the data tape recorders for the NLP project. The sound of the shocks was just a doorbell with the bell removed. The whole thing was held together with a pair of bookshelf brackets exactly like what I used for cheap and light rigidity in Freedom Flies.

I’ve been thinking about building a copy of the Milgram box since early in the Covid pandemic, but over exactly two years it never occurred to me that my prior work in building fake science for art – NLP, Character Input, and the massive instrument panels of Control – was almost exactly what Milgram had built. I was doing it in an art context, he was doing it in an experimental psychology context, but the objects were as identical as could be imagined, even with decades between them.

A day later, I’m not sure how I feel about this. I think this adds depth to the project, but I nonetheless feel a bit confused, if not deflated. I’m used to being the one who builds simulacra, lies designed to reveal bigger truths. I’ve never built a simulacrum of a simulacrum, and I’m worried that it might be more recursive a project than I usually gravitate toward, like the brief craze in the 2000s to remake older films frame-for-frame. I guess I have learned that I prefer honest moral clarity in my fakes. Balanced with this vauge sense of whipping back the curtain only to find that I was the Wizard of Oz, I did feel a material connection to the work that I hadn’t expected. Complicated day!